Roger was the name given to the white lead, drawing by Piffard

Roger was the name given to the white lead, drawing by Piffard Alkali worker drawing ash from the furnace, drawing by Piffard

Alkali worker drawing ash from the furnace, drawing by Piffard Alkali workers, drawing by Piffard

Alkali workers, drawing by Piffard Alkali worker stirring caustic-pots, drawing by Piffard

Alkali worker stirring caustic-pots, drawing by Piffard A band-knife used in the shoe-making process, drawing by Piffard

A band-knife used in the shoe-making process, drawing by Piffard Lead workers, drawing by Piffard

Lead workers, drawing by Piffard Blue-bed women with trucks of lead, drawing by Piffard

Blue-bed women with trucks of lead, drawing by Piffard Interior of white lead factory, drawing by Piffard

Interior of white lead factory, drawing by Piffard Early death was common amongst lead workers, drawing by Piffard

Early death was common amongst lead workers, drawing by Piffard Woolcomber, drawing by Piffard

Woolcomber, drawing by Piffard Poor conditions have taken their toll on this woolcomber, drawing by Piffard

Poor conditions have taken their toll on this woolcomber, drawing by Piffard

Sweated factory work differed from sweating in a domestic setting only in the fact that no middlemen were involved. Long hours, low pay and poor, often dangerous, conditions were common to both. Sweated labour was, in fact, widespread throughout Britain. It existed in factories, docks offices, shops and laundries, in work on farms, roads, railways, canals and at sea. Sweating featured in the manufacture of such goods as hollow-ware, bricks, pickles, confectionery, cutlery, jute and matches.

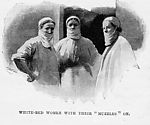

The drawings shown here, record the conditions found amongst alkali workers, lead workers, shoemakers and woolcombers . They were produced by Harold Piffard, a well-known society artist. In 1897 he had accompanied Robert Sherard, as he travelled around the country investigating the conditions of the working poor. His drawings illustrated the subsequent publication of Sherard's findings, under the heading of "The White Slaves of England."

Lives were cut tragically short in many industries. The alkali workers of St Helens risked being poisoned by chlorine gas or boiled alive in caustic vats. The woolcombers of Bradford had their lungs filled with dust that would eventually kill them, and the lead workers of Newcastle were slowly, but surely, poisoned.

In a number of industries employers would insist on their workforce attending at the factory to wait for work to come in, during which time they would not be paid. On occasion they could wait all day for an order to come in, only to be sent home without pay. Other employers would promise a particular piecework rate for an item, only to reduce the amount when workers arrived to do the job, leaving them little option but to accept it.

Practices such as these were widespread, because few of the controls we have today were in existence then.The Factory Acts had set minimum standards and had established a regime of inspection, but the authorities were often slow to acknowledge the dangers inherent to an industry. Also, many workers were afraid to speak out, partly through fear of reprisals by employers, and partly through fear of destroying an industry they were dependent on for a living. Ibsen’s play “Enemy of the People”, written in 1882, dealt with exactly this issue.

There was also a reluctance, on the part of some working in the most dangerous industries, to complain or to appear weak. It is clear from reading the accounts of some people, that they took pride in the fact that they were able to endure the most appalling of conditions without complaint.

Many newspapers at the time continued to defend local industry, despite the growing body of evidence that sweating was damaging, not only to the workers, but to the public at large. Whether or not this was as a result of an unwillingness to accept the evidence, or that some newspaper owners had a vested interest in perpetuating sweating is open to debate.

The Trade Union Movement did, eventually, enable workers to receive a fair wage. But, at the end of the Victorian age, unions were only just gaining strength and they too had to battle against corruption and intimidation.

It would be re-assuring to think that sweating, low pay and poor conditions had come to an end. Unfortunately, as we saw from the loss of life, in recent years, amongst the cockle pickers of Morecambe Bay, to some extent it continues today. As for dangerous industries, they have not disappeared. Many are now located in the Developing World, where Health and Safety legislation has yet to arrive.

Rollover the captions in the box to see the available images in thumbnail format, click the caption to see the full-size image

| Reference: | 728 |

| Keywords: | |

| Archive Ref: | |

| Updated: | Wed 25 Jun 2008 - 1 |

| Interpretation written by | Louis Howe |

| Author's organisation | Curatorial |

| Organisation's website |