Cannon, manufacturer of gas cookers, catalogue cover 1920s

Cannon, manufacturer of gas cookers, catalogue cover 1920s Cannon Challenge gas cooker, 1920s

Cannon Challenge gas cooker, 1920s Cooker advertisement, County Express, Jan 9th 1937

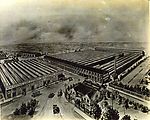

Cooker advertisement, County Express, Jan 9th 1937 Bird's eye view of the Revo factory in Tipton in the 1920s

Bird's eye view of the Revo factory in Tipton in the 1920s Revo cooker assembly bay

Revo cooker assembly bay Revo electric fires and irons bay

Revo electric fires and irons bay Revo stove enamelling bay

Revo stove enamelling bay Goblin Wizard electric vacuum 1930s (held at the Black Country Living Museum)

Goblin Wizard electric vacuum 1930s (held at the Black Country Living Museum) Gas iron, Arden Hill Company (held at the Black Country Living Museum)

Gas iron, Arden Hill Company (held at the Black Country Living Museum)  Electric iron box, Cooperative Wholesale Society (held at the Black Country Living Museum)

Electric iron box, Cooperative Wholesale Society (held at the Black Country Living Museum) Singer sewing machine, 1870 (held at the Black Country Living Museum)

Singer sewing machine, 1870 (held at the Black Country Living Museum)

“Simply switch on” – that was the difference between the old way of doing things in the home and the new. “Simply switch on” was a common phrase in almost every electrical appliance instruction leaflet from the 1920s to the 1950s. It meant that you had invested in a piece of new domestic gadgetry, and now that it had been delivered, unwrapped, assembled and plugged in, that old domestic chore would be transformed and your way of life would be dramatically improved. Without necessarily understanding the technology of it, you were confident that the new machine would save time and effort, and even better, was a symbol of your new prosperity and modernity. In short, you were investing in a piece of the twentieth century that would have been beyond the dreams of your parents.

Despite the advances made, however, it should be remembered that for many, housework between the two world wars continued to be done by hand.

Before electricity, the most sophisticated machines in the home, the sewing machine, carpet sweeper and mangle were all hand-operated. The hub of any late-Victorian household was the coal-fired range. It cooked the food, heated the water and kept the kitchen warm. However, the range made the kitchen a hot place to work in the summer, and it was dirty, temperamental and time consuming to use and to clean. It was not until after the First World War that easy-to-clean enamel, gas and electric cookers were introduced.

Laundry was done by hand. The family’s clothes were boiled in a large copper cauldron set over its own fire in the scullery or outhouse. Clothes would be pounded with a "dolly", rubbed on a washboard, wrung out through a mangle and then ironed using flat irons heated on the kitchen range. It was exhausting work and very time consuming. Any family that could afford to do so would send their washing out to be done professionally.

It was in these commercial laundries that many of the technical innovations were first made, and were later taken up and developed into domestic washing machines. Only after 1900 was there a significant advance, with the application of an electric motor. The twin-tub machine evolved in the 1920s. It combined a washing machine with a spin drier. It quickly became popular in America, but in Britain they were considered an expensive luxury and did not become affordable and popular until the 1950s.

Dust was the great enemy of the Victorian home. Oil and gas lighting, the coal-fired range and the coal-filled grates created dust, which harboured germs, harmed fabrics and irritated noses. Against this foe there was an impressive battery of brushes; there were banister brushes, stove brushes, carpet whisks and numerous other specialised creations. Yet these did little more than stir up the dust and redistribute it around the house. Carpets could be taken outside and beaten, but this took time and needed a great deal of energy. Finding an effective method of sweeping up dust became one of the "holy grails" of late-Victorian invention.

Almost all the electrical appliances that are taken for granted in the home today were in existence in some form before 1914. Indeed, the mechanical principles embodied in some electrical machines, such as vacuum cleaners, dish washers and automatic washing machines were in existence by the end of the Victorian era. Appliances were not widely available however. They were very expensive, in some cases badly designed, and in 1910, less than 2% of British homes were wired for electricity.

Real progress in developing a machine that would suck or blow dust off a surface into a receptacle was not made until 1901. H. Cecil Booth, an English engineer, developed his proto-vacuum cleaner. It was a vast contraption, looking more like a horse-drawn fire engine than a domestic appliance. It was powered by a five horse-power piston engine, which could be run on either electricity or petrol. It could be summoned for special spring cleaning duty. The engine would be drawn up outside the house, Hoses with specially designed nozzle attachments would be run up through the windows of the house by a troop of cleaners, all men, in the uniform of the British Vacuum Cleaner Company. The dust was sucked up and off into the cylindrical body of the machine out in the street. The effects of the procedure were highly dramatic. Some Edwardian hostesses arranged tea parties so that their guests might witness the event at close quarters.

The development of a portable machine for easy domestic use happened on the other side of the Atlantic. W.H.Hoover developed “The Electric Suction Sweeper” in 1908. It was taken up in America almost immediately. In Britain its progress was slower. Electricity was not readily available in most homes until after the First World War.

After 1920, both the standards of appliance design and their availability began to rise as the market for electrical goods steadily increased. A major manufacturer of electrical goods at this time was Revo, based in Tipton. By 1939, the market for smaller, cheaper appliances in particular had grown significantly for a variety of reasons:-

The private housing boom of the inter-war years brought affordable houses with electricity to the middle classes for the first time. By 1931 the number of homes with electricity had risen to 33%, increasing to 67% by 1939, comprising 4 million new houses, and about half the existing housing stock, which had “gone electric”. The period 1930 – 1939, therefore, first saw electricity available to the majority.

Electricity distribution, which had developed on a localised and sporadic basis, became standardised and reliable with the setting up of the National Grid between 1928 and 1935. It was developed under the control of the Central Electricity Board that had been established under the Electricity Supply Act of 1926. Household electricity supplies expanded greatly, replacing coal, gas, candles and human effort.

The cost of electrical appliances fell during the 20s and 30s as the British electrical appliance industry expanded, spurred on by competition from the USA, and the development of new materials and new manufacturing techniques.

The new hire-purchase system meant that the high cost of an electrical appliance could be spread over a long period.

Persuasive, door-to-door sales techniques were used to promote electrical appliances by organisations such as the Electrical Development Association (EDA) and the Electrical Association for Women (EAW). Electrical goods could also be bought from local bicycle, hardware and ironmongery stores, in town department stores or from local electricity board showrooms.

Electrical appliances were accepted as modern servant replacements, allowing middle-class women to do their own housework, without losing their dignity.

Rollover the captions in the box to see the available images in thumbnail format, click the caption to see the full-size image

| Reference: | 750 |

| Keywords: | |

| Archive Ref: | See metadata |

| Updated: | Wed 23 Apr 2008 - 0 |

| Interpretation written by | Barbara Harris |

| Author's organisation | |

| Organisation's website |