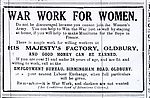

Advertisement in the Dudley Herald, 1st June 1918

Advertisement in the Dudley Herald, 1st June 1918 Sunbeam Ambulance 1917

Sunbeam Ambulance 1917 HM Hobson Ltd, 'Accuracy' Works, Wolverhampton, 1914-1918

HM Hobson Ltd, 'Accuracy' Works, Wolverhampton, 1914-1918 Machine Gun Carrier, Clyno Engineering Co. 1919

Machine Gun Carrier, Clyno Engineering Co. 1919 Machine Gun Corps, 1919

Machine Gun Corps, 1919

Within weeks the First World War was swallowing vast numbers of men and resources. Women were needed to take on the jobs traditionally done by men. All classes of women were mobilized. Wanting to "do their bit", they moved into areas of public, commercial and industrial life.

For Black Country women the experience was perhaps less extraordinary than for women in other parts of the country. Large numbers already worked in engineering, metalwork, chemical and vehicle manufacture. Holding down a job at the same time as running a home and raising a family was nothing new.

At the beginning of the war large numbers of women lost their jobs, particularly in the luxury trades. The Government showed little interest in recruiting women into war work at first. In an attempt to improve the situation Queen Mary established a volunteer Needlework Guild. Its members made items providing additional comforts for soldiers and sailors, for the sick and wounded, and their families, and for those unemployed because of the war. They also received, sorted, packed and distributed gifts from all over Britain and from allied and neutral countries.

Queen Mary's Work for Women Fund was also created to provide paid work for as many as possible of the women thrown out of work by the war. The Queen asked Mary Macarthur to serve as Honorary Secretary of the Fund. A string of workshops were set up, providing work for over 9,000 women. They were paid 10 shillings (50p) for a forty hour week.

In May 1915 news that troops were short of high explosives shocked the country. A Ministry of Munitions was set up, headed by David LLoyd George. Women were actively encouraged to take jobs in the munitions factories. The work was well paid, but extremely dangerous. Munitions girls were called "Canaries" because handling TNT turned their faces and hands yellow. Over 400 women died from overexposure to TNT, and explosions causing fatalities were not uncommon.

In the following year, compulsory male conscription was introduced, making the employment of women even more important. Restrictions to particular trades were lifted. The number of female employees in public transport increased ten-fold. Administrative, commercial and educational sectors also saw big rises in female labour. They worked in sawmills, drove lorries, bottled beer and manufactured furniture. They worked in foundries, cement factories, jute and wool mills, tanneries and car factories. They were riveters in shipbuilding yards and could be found in quarrying, surface mining and brickmaking. They worked on the railways, in power stations, gas works and on sewage farms. They were park attendants and chimney sweeps. Only underground mining, work on the docks and steel and iron smelting were still all male preserves.

Elsewhere, women became police officers and joined special units of the armed forces. Early in 1917, women were invited by the War Office to join the armies overseas, replacing, as far as possible, the men in civilian occupations at the bases. The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAACs) was established in July 1917. The Admiralty and Royal Air Force followed the example, and established the Women’s Royal Navy Service (Wrens) in November 1917, and later the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAFs).

Other women joined the Land Army, which was set up to make sure the country had a plentiful supply of home-grown food. They were poorly paid, worked in difficult conditions, often suffered from loneliness on isolated farms, and were least under the control of the authorities. At first farmers were not very keen to employ women, but by 1918 there were over 300,000 women working on the land.

One of the great feats of the war was the mobilization of the nursing services. Within ten days of the outbreak of war, twenty-three Territorial General Hospitals in different parts of the country and 3,000 Territorial nurses, were ready to receive wounded. Others were sent to work, and sometimes die, behind the front lines in France.

It was a long war, but women always understood that their new work was temporary, and that they would have to step aside for returning soldiers. By summer 1920, over 60 per cent of all women who entered employment during the war had left it again. As unemployment grew after the war, married women found themselves further discriminated against, as many employers introduced a marriage ban.

Despite some backward steps, the role of women had moved forward. There was a huge increase in trade union membership, making it necessary for unions to pay more attention to women's employment issues. Opportunities had been opened up and many prejudices overcome. In February 1918, the Representation of the People Act gave votes to 6 million women, who owned property and were over the age of 30. Some historians suggest that it was granted in recognition of the contribution made by women to the war effort.

Rollover the captions in the box to see the available images in thumbnail format, click the caption to see the full-size image

| Reference: | 752 |

| Keywords: | |

| Archive Ref: | |

| Updated: | Wed 23 Apr 2008 - 1 |

| Interpretation written by | Barbara Harris |

| Author's organisation | |

| Organisation's website |