Dispatch riders wait for instructions outside TUC headquarters

Dispatch riders wait for instructions outside TUC headquarters Pickets at London docks

Pickets at London docks Food lorry with an armoured car escort

Food lorry with an armoured car escort Rowley Regis Trades and Labour Council set up an emergency committee

Rowley Regis Trades and Labour Council set up an emergency committee Report from Walsall Trades Council on progress of the strike

Report from Walsall Trades Council on progress of the strike Newspaper coverage following the end of the General Strike

Newspaper coverage following the end of the General Strike Miners faced a cut in wages and an increase in hours

Miners faced a cut in wages and an increase in hours Laws introduced following the General Strike

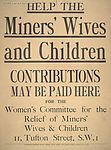

Laws introduced following the General Strike Many miners and their families had to rely on charity

Many miners and their families had to rely on charity

In May 1926, millions of trade unionists staged an historic General Strike that brought Britain to an almost complete standstill. It lasted nine days before the leaders of the Trades Union Congress capitulated to the Government and abandoned the strike.

There were problems in the economy after the First World War. The Government had returned to the Gold Standard in 1925, tying the value of the pound to the amount of gold in the Bank of England. This caused a depression and reduced exports, especially of coal. There was a concerted effort on the part of employers in Britain’s declining staple industries to increase productivity and cut wages.

The coal industry, which accounted for a sixth of the male labour force, became a target for reorganisation. In 1925 the mine owners announced their intention to reduce miners’ wages. The TUC promised to support miners in the dispute. The Conservative Government decided to intervene, and provided the necessary money needed to bring miners’ wages back to their previous level, thus averting a strike. This event became known as Red Friday, because it was seen as a victory for the working classes.

The subsidy was a temporary measure, however, put in place to give a Royal Commission (the Samuel Commission) time to look into the problems facing the mining industry. It reported that the industry was in need of re-organisation, but rejected nationalization as a solution. It recommended the withdrawal of the Government subsidy and a reduction of miners’ wages.

Following the report, mine owners published new terms of employment, in which they stated their intentions to end national wage agreements, extend the working day, and at the same time reduce wages by 13%. If the miners refused to accept the new conditions from the 1st May, they would be locked out of the pits. Miners’ representatives, however, were not informed of the new conditions until 1.15 pm on the 30th of April, leaving no time for union leaders to consult their members.

A Conference of the TUC, held on May 1st, pledged its support for the miners. It announced that a General Strike would be called in two days time should an agreement on miners’ wages and conditions not be reached. The TUC decided to bring out workers in what they regarded as the key industries; railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers, a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later were engineers and shipyard workers called out. Frantic efforts were made to avert the strike. The two sides were close to agreement when Stanley Baldwin broke off negotiations, following the refusal of Daily Mail printers to print a leading article denouncing the strike. The TUC knew nothing of the action, but the Government saw it as a challenge.

The strike received overwhelming support. The TUC’s strike newspaper, “The British Worker”, which was printed on the Daily Herald’s presses, reported on the situation in the Black Country. The first issue on Wednesday 5th May reported that the stoppage in Birmingham and surrounding districts was complete. Not a man on the railways or other transport was working. The biggest trouble was to keep at work those who were not involved. A special report to the TUC from the Walsall Trades Council National Industrial Crisis Committee on 6th May stated that the position in Walsall was “splendid”. A wonderful demonstration had been held with a huge meeting. All were out who had been called out. In addition, several thousand engineers had decided that they were on transport work and had joined the strike.

One of the most urgent tasks for the unions was to establish lines of communication. Those on strike needed news and instructions, while organisers needed feedback on the local response to the call for sympathy action. Very few local union officials had telephones in 1926 and the post was interrupted by the cancellation of mail trains, so the TUC relied on a network of dispatch riders sent out from TUC headquarters in Eccleston Square, London. Local networks of messengers were also set up, travelling by bicycle, motorbike, occasionally by car, more often on foot, to circulate local and regional news.

Local arrangements were made through various Trades Councils. Where there was no Trades Council, special Councils of Action were set up. They were responsible for establishing local networks of messengers, coordination between unions, the collection and dissemination of news, organisation of meetings, preparation of propaganda, ensuring food supplies, issuing of permits giving permission to pass pickets, supplementation of pickets of individual unions by central teams, welfare and defence of anyone arrested, organisation of social and money raising activities. Almost every urban area saw meetings and demonstrations perhaps larger than they had seen before. Labour MPs returning to their constituencies on the Saturday before the strike began, found crowds gathering around the banners of local parties and trade unions. Speeches were made in Cradley Heath by MPs Mr A Short and Mr C Sitch in support of the strikers.

The Government was ready and had used the nine months during which the subsidy was paid to make preparations for the conflict. Ten Civil Commissioners were appointed with full authority under the Emergency Powers Act to run the ten regions into which Britain was to be divided. A volunteer strike-breaking body was formed, the “Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies (OMS). At the beginning of the General Strike it had lists of over 100,000 volunteers. Many, who were willing to be strike-breakers and take over the running of essential services, came from the middle-classes. They were frightened by incidents of violence and the support the strike was receiving from the communists. Others were just fulfilling boyhood dreams to be a train driver or bus driver.

There was real potential for catastrophe with amateurs taking on essential roles. One train driver arrived for work to find he had a volunteer fireman, dressed in a silver grey suit, with silver grey spats, a velour hat and yellow gloves, with the engine fired up and the boiler near to explosion.

At the same time the Government made its own military preparations. The Navy was positioned at strategic points around the coast, and troops were stationed throughout the country, especially near major ports and large centres of population.

Strike-breakers and volunteers came under attack. Slops were emptied over special constables, bus tyres were let down and a few buses set on fire. On 6th May, there were fights between strikers and police in London, Glasgow and Edinburgh. On the 7th, police and strikers clashed in Liverpool, Hull and London. Engines were sabotaged and trains attacked. On the London – Glasgow line, at the bottom of an incline, the rails were smeared with grease, so that when the train reached that point, the wheels could not grip and no progress could be made. On the main Edinburgh line, strikers dismantled part of the track, expecting to derail a goods train. It was, in fact, the Flying Scotsman. Fortunately it had been travelling at a crawling pace, so that, although the engine turned over onto the embankment, no-one was seriously hurt. An eye-witness at the scene said that one man’s luggage had landed on his foot and injured it. So many of his fellow passengers rallied round and plied him with whiskey and brandy to kill the pain, that when he arrived at hospital he was very merry indeed.

In some cases the treatment of the strikers was harsh. Joseph Ball, a miner of Cross Street, Dudley was given one month’s hard labour for allegedly assaulting two police officers and committing an offence against the Emergency Powers Act. He incited the crowd by shouting, “Come on lads. Let’s have a go! We’re not frightened of you.” Eight saboteurs were caught and sentenced to eight years imprisonment. When asked why they did it, one replied that he had nothing else to lose.

Throughout the strike, the unions made it clear that theirs was an industrial dispute, and in no way a challenge to the constitution or an attempt to undermine parliamentary democracy. Baldwin, the Prime Minister, saw it very differently, suggesting that the strike was bringing the country nearer to civil war than it had been for centuries. Many agreed with him, none more so than Winston Churchill, who was given the responsibility of publishing the Government’s official propaganda newspaper, the British Gazette”, printed on the presses of the Morning Post. The cabinet also discussed taking over the BBC for the duration of the strike, but the company, although under pressure from the Government, managed to remain largely independent.

Secret talks continued between the TUC Negotiating Committee and Herbert Samuel, chair of the 1925 Royal Commission. The result was the Samuel Memorandum, a formula for a settlement. The Memorandum, however, was merely a repeat of the1925 Royal Commission proposals. Without consulting the miners, and much to their surprise, the TUC accepted the Samuel Memorandum, and the strike was called off after 9 days.

The Strike had been closely followed in the world’s press. International sympathy for the strike was high. A boycott of the UK was discussed at a meeting of the International Transport Workers’ Federation and the Miners’ International Federation at Ostend on 8-9 May, but before any action could be agreed, the General Strike was at an end.

The miners felt betrayed, and they rejected the “settlement” entirely. They went on to fight alone for a further six months, until they were starved back to work. When union strike pay ran out, the miners’ had to turn to the Poor Law Guardians. Some Boards tried to deny any responsibility for men on strike, but were compelled by public opinion to support wives and children. The Walsall Guardians considered that a maximum of 30 shillings (£1.50) a week was sufficient to maintain the largest family. The Stourbridge Guardians set their maximum at 26 shillings (£1.30) per week. Relief was arbitrary and varied from town to town. In June the Vicar of Cradley complained that the miners in that town were receiving no relief from the Guardians. In the absence of strike pay and Poor Law relief, miners had to depend on fundraising. Substantial amounts came from the Miners’ International, contributions having been received from all over the world. Volunteer groups provided meals for miners’ children and set up soup kitchens.

Despite the support they received, at the end of November the miners were forced to give in. Wages were cut and fixed on a district rather than a national basis. The minimum wage disappeared, and the working day was extended from 7 to 8 hours. In the end they had been forced to accept what they could have had before the strike started.

After May 12th, there was widespread victimization, especially in printing and the railways. Government reaction was punitive. It introduced the Trades Disputes and Trades Union Act in 1927 by which general strikes and most sympathy strikes became illegal. The Act also outlawed the automatic political levy from members whose trade union was affiliated to the Labour Party, replacing it with a requirement to “contract in”.

The General Strike was a remarkable demonstration of working class solidarity, but it took a decade for the mass labour movement to recover from such a crushing defeat. All unions that had taken sympathetic action suffered financially because of the amounts paid out of their funds for strike pay or unemployment benefit. Trade Union funds had dropped by £4 million by the end of 1926, and trade union membership fell by over half a million in 1927 alone. Membership of the TUC fell from 5.5 million in 1925 to only 3.75 million in 1930.

Rollover the captions in the box to see the available images in thumbnail format, click the caption to see the full-size image

| Reference: | 753 |

| Keywords: | |

| Archive Ref: | |

| Updated: | Wed 23 Apr 2008 - 0 |

| Interpretation written by | Barbara Harris |

| Author's organisation | |

| Organisation's website | |

| Source | G.J. Barnsby, Socialism in B'ham and the Black Country, 1998 |

| Source | TUC History Online |

| Source | BBC Eyewitness 1920 - 1929 (Audio accounts) |

| Source | All images - TUC archives |