Dispatch riders wait for instructions outside TUC headquarters

Dispatch riders wait for instructions outside TUC headquarters Pickets at London docks

Pickets at London docks Food lorry with an armoured car escort

Food lorry with an armoured car escort Rowley Regis Trades and Labour Council set up an emergency committee

Rowley Regis Trades and Labour Council set up an emergency committee Report from Walsall Trades Council on progress of the strike

Report from Walsall Trades Council on progress of the strike Newspaper coverage following the end of the General Strike

Newspaper coverage following the end of the General Strike Miners faced a cut in wages and an increase in hours

Miners faced a cut in wages and an increase in hours Laws introduced following the General Strike

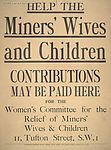

Laws introduced following the General Strike Many miners and their families had to rely on charity

Many miners and their families had to rely on charity

In May 1926, a General Strike brought Britain to a standstill. It lasted nine days, but left the miners to carry on the fight alone for a further six months.

There were problems with the economy following the First World war. Employers tried to increase productivity and at the same time cut wages.In 1925 the Government stepped in with a subsidy to avoid the miners going on strike. But the measure was only temporary. When it came to an end, the Samuel Royal Commission recommended a cut in wages of 13% and a lengthening of the working day. The miners refused to accept the new conditions and were locked out of the pits.

On May 1st 1926, the Trade Union Congress (TUC) pledged its support for the miners. Workers in key industries were called out on strike. Railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders and iron and steel workers came out in support, followed by engineers and shipyard workers.

Across the country the response was overwhelming. The stoppage in Birmingham and the Black Country was reported as complete. Trades Councils, and specially formed Councils of Action set up local networks of messengers, organised meetings and pickets, ensured food supplies, raised money and took care of the welfare and defence of anyone arrested.

The Government had spent the nine months during which the subsidy was paid to prepare for the strike. A volunteer strike-breaking body was formed, the "Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies (OMS), At the beginning of the strike there were over 100,000 volunteers. At the same time the Government positioned the Navy at strategic points around the coast, and troops were deployed in readiness throughout the country.

Strike-breakers and volunteers were attacked. Slops were emptied over special constables, bus tyres were let down and a few buses set on fire. On 6th May, there were fights between strikers and police in London, Glasgow and Edinburgh. On the 7th, police and strikers clashed in Liverpool, Hull and London. Engines were sabotaged and trains attacked. On the London – Glasgow line, at the bottom of an incline, the rails were smeared with grease, so that when the train reached that point, the wheels could not grip. On the main Edinburgh line, strikers dismantled part of the track, expecting to derail a goods train. It was, in fact, the Flying Scotsman. Fortunately it had been travelling at a crawling pace, so that, although the engine turned over onto the embankment, no-one was seriously hurt. An eye-witness at the scene said that one man’s luggage had landed on his foot and injured it. So many of his fellow passengers rallied round and plied him with whiskey and brandy to kill the pain, that when he arrived at hospital he was very merry indeed.

Strikers involved in such actions were treated very harshly. Eight men found guilty of sabotage were given eight year prison sentences. When asked why they did it, one replied that he had nothing else to lose.

While the strike continued, secret talks were being held between the TUC and Herbert Samuel, the chair of the 1925 Royal Commission. Without consulting the miners, the TUC agreed to call off the strike, but the settlement was no better than that at the beginning of the dispute.

The miners felt betrayed. They rejected the settlement, and went on to fight alone, until they were starved back to work six months later. Wages were cut and fixed on a district rather than a national basis. The minimum wage disappeared, and the working day changed from seven to eight hours. In the end the miners had been forced to accept what they could have had before the strike started.

Rollover the captions in the box to see the available images in thumbnail format, click the caption to see the full-size image

| Reference: | 753 |

| Keywords: | |

| Archive Ref: | |

| Updated: | Wed 23 Apr 2008 - 0 |

| Interpretation written by | Barbara Harris |

| Author's organisation | |

| Organisation's website |