TUC appeal in support of textile workers, 1932

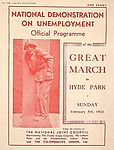

TUC appeal in support of textile workers, 1932 Poster advertising unemployment demonstration, February 1933

Poster advertising unemployment demonstration, February 1933 National Unemployment Demonstration 1933

National Unemployment Demonstration 1933

On October 24th 1929, nearly 13 million shares changed hands on the New York Stock Exchange as Wall Street crashed, and Black Thursday secured its place in the history books. This signalled the beginning of an economic downturn, centred in North America, but the effects of which were felt around the world, particularly in industrialized countries. The British working class experienced some of its darkest days in the following decade.

The Great Depression of the 1930s hit the United Kingdom at a time when it had not yet recovered from the effects of the First World War. Britain had financed the war effort largely through the sale of foreign assets. The resulting loss of foreign earnings left the British economy more dependent on exports and, therefore, more vulnerable to a downturn in world trade. However, the war had eroded Britain’s trading position through disruptions to trade and losses of shipping. Overseas customers for British products had been lost, especially in the traditional industries such as textiles, steel and coalmining, industries which, therefore, were already experiencing recession. Unemployment at this time remained at a steady one million.

In April 1925, the Conservative Chancellor, Winston Churchill, restored the Pound Sterling to the Gold Standard at its pre-war exchange rate. This put it at a level which made British exports more expensive on the world’s markets. To offset the effects of the high exchange rates, export industries tried to cut costs by cutting workers’ wages, provoking the General Strike of 1926.

The Wall Street Crash in New York, and the ensuing US economic collapse, caused world trade to contract further. Governments faced financial crisis as American credit dried up. Many countries responded by erecting trade barriers and tariffs, which exacerbated the situation by further hindering trade. In Britain, the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, introduced tariffs at a rate of 10% on all imports, except those from countries of the British Empire.

The effects on industrial areas in Britain were immediate and devastating, as demand for British products collapsed. By the end of 1930, unemployment had more than doubled from one million to two and a half million (20% of the insured workforce.)

The May Report of July 1931, which urged public sector wage cuts and large cuts in benefits, split the Labour Government, and led to its resignation. It was replaced by a National Government, which immediately instituted a draconian round of public spending and wage cuts. Public sector pay and unemployment benefit were cut by 10% and income tax was raised. These measures reduced purchasing power in the economy and worsened the situation. By the end of 1931 unemployment had reached three million.

The overall picture for the British economy in the 1930s was bleak, but the effects of the depression were uneven, both geographically and between the classes.

As always, not everyone suffered. For the wealthy things continued much as before. The BBC Radio 4 broadcast "In Our Time" on 11th March 1975 recalls Lady Astor’s fabled parties held at the time, which she justified as a means of gathering influential people together in order to get things done, rather than as simply a matter of idle socialising. In the same broadcast, Robert Boothby, Conservative MP for East Aberdeenshire, recalled being at one of the parties, where only a little white wine was allowed, Lady Astor being a militant teetotal prohibitionist. Oswald Moseley and his wife were invited, and had brought a petrol can of dry martini, which the guests drank in their bedrooms before going down to dinner. The "admirable" butler had put it on ice.

Some previously secure middle class families had to tighten their belts. In "The Hungry Years" on the Home Service in February 1957, a middle class woman recalled the effects of the Depression on her household. She sent a lot of servants away and had to learn to cook, and discovered that all the children were marvellous butlers, able to clean the silver better than it had ever been cleaned before. It was all a little grim for the grown-ups, she said. Her husband was terribly depressed, and didn’t want to go to the city at all; he thought it was all too dreadful!

It was the casual and waged workers who bore the brunt of the economic downturn. Even here, however, the impact was uneven. In London and the south east of England unemployment was initially high at 15%, but the later years of the decade saw a rise in prosperity in these areas. A housing boom was fuelled by low interest rates. New industries emerged, in the south and the Midlands, which prospered from large-scale electrification of housing and industry. Mass-production methods brought new products such as electric cookers, washing machines and radios into the reach of the middle classes.The motor industry also prospered in the 1930s, the number of cars on British roads doubling within the decade. As a result, parts of Birmingham, Coventry and Oxford escaped the very worst effects of the Depression.

It was the North of England, South Wales, and Central Scotland, which suffered the most severe effects. The traditional industries of coalmining, shipbuilding, steel and textiles were concentrated in these areas. Between 1929 and 1932 ship production declined dramatically, which in turn affected all the supply industries such as steel and coal. Much of the heavy chain made in Cradley Heath, in the Midlands, for example, was made for the shipbuilding industry, and suffered a decline as a result. In some towns and cities in the north east unemployment reached 70%. Amongst the worst affected towns was Jarrow, which caught the public imagination when 200 unemployed men of the town marched the 300 miles to London to hand in to Parliament a petition bearing 11,572 signatures.

In the worst hit areas, families were left destitute, relying on soup kitchens and other charity. Being unemployed, sometimes for years, was debilitating at best, but to this was added the humiliation of the Means Test, which was introduced in 1931.

The National Government decreed that all unemployed workers, who had received 26 weeks of benefit, would have to undergo a Means and Needs Test. The questions they were asked were searching, personal and often impertinent, but failure to satisfy official curiosity carried the penalty of having benefit reduced or cut off altogether.

An unemployed worker was compelled to state how much every member of the family earned; what income came into the household from army pensions, trade union benefits, widow’s or old age pension, assistance from relatives, income from lodgers, keeping poultry, Post Office savings etc. The Public Assistance Committee, which administered the Test, employed a special army of investigators who made personal visits to homes, questioned next-door neighbours, and even contacted employers to check that any earnings declared were correct. Any income, from whatever source, including the sale of ‘non-essential’ items, was taken into account. In its first four months of operation the Means Test was being applied to over a million unemployed. By 1932, 377,000 men had been struck off from receiving any kind of benefit.

In "The Hungry Years" broadcast, one unemployed man remembered with anger the shame of having to go, "cap-in-hand", before a means test tribunal. He had been walking the streets for six months trying to find work, but there were no jobs to be had. He said that he was examined by four well-fed men who had probably been in employment all of their lives. They saw him as just lazy and work-shy. Their first question was, "Why have you been out of work?" as though the answer was not obvious.

The National Unemployed Workers Movement produced a pamphlet called, "Mass Murder: an exposure of the Means Test" in which it detailed many cases of hardship, of family breakdown and even suicide. A Grimsby man had a wife and three children. He received unemployment benefit of 25 shillings and three pence (£1.27). His son earned 15 shillings and three pence a week (76p). His daughter earned a pound. Under the Test his benefit was cut off. A family of five was forced to exist on the earnings of the son and daughter. In Earby in Yorkshire an ex-serviceman and his two sons were out of work. All three lost their benefit because the wife was earning two pounds a week, and he was receiving ten shillings (50p) army pension, having been injured in the Great War.

Official contempt for the unemployed culminated in labour camps. It was believed that prolonged unemployment had robbed many men of the physical fitness and attitude of mind to enable them to undertake heavy work. Work in the camps included forest clearing, road-making, drainage, quarrying, boot-making, carpentry and metal work. The aim was to make men more employable, despite the fact that there were no jobs available. Men were forced to leave their families and live at the camps, if they wanted their wives and children to receive any kind of assistance. The regime was military in nature; the food insufficient. Pay was just 4 shillings (20p) a week from which deductions were made for petty offences. By 1938, 35 such labour camps, quickly dubbed "slave camps", had been established. Over 120,000 men were obliged to attend.

Rearmament in response to the threat from Nazi Germany helped to stimulate the economies of many countries around the world. By 1937, in Britain, unemployment had fallen to one and a half million. With the outbreak of war in 1939, unemployment was effectively at an end.

Rollover the captions in the box to see the available images in thumbnail format, click the caption to see the full-size image

| Reference: | 755 |

| Keywords: | |

| Archive Ref: | |

| Updated: | Wed 23 Apr 2008 - 1 |

| Interpretation written by | Barbara Harris |

| Author's organisation | |

| Organisation's website |