TUC appeal in support of textile workers, 1932

TUC appeal in support of textile workers, 1932 Poster advertising unemployment demonstration, February 1933

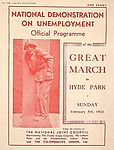

Poster advertising unemployment demonstration, February 1933 National Unemployment Demonstration 1933

National Unemployment Demonstration 1933

The Wall Street stock exchange crash in October 1929 signalled the beginning of an economic crisis that was felt around the world.

The Great Depression of the 1930s hit Britain at a time when it was still trying to recover from the First World War. Trade had not recovered, particularly in the traditional industries such as textiles, steel and coalmining. Unemployment stood at about one million.

In April 1925, the Conservative Chancellor, Winston Churchill, restored the pound to the Gold Standard at pre-war rates. As a result British exports became more expensive and trade declined even further. Many employers tried to cut costs by cutting wages, leading to the General Strike in 1926.

Following the Wall Street Crash, American credit dried up and many countries, including Britain, imposed trade barriers and tariffs, which served to hinder trade yet again.

The effect on industrial areas in Britain was immediate and devastating. By the end of 1930, over two and a half million people were out of work. In 1931 the National Government cut public sector pay and unemployment benefit by 10%, and increased income tax. Unemployment reached three million.

People's experiences of the Depression were very different, depending on where they lived and to which class they belonged. For the wealthy, life continued much as before. Some middle class families found that they had to tighten their belts, but it was the casual and waged workers who bore the brunt of the economic crisis.

Even here the impact was uneven. London and the south east of England saw a rise in prosperity during the later years of the decade. New industries emerged, in the south and the Midlands, which prospered with the large-scale electrification of housing and industry. Mass production methods brought new products such as electric cookers, washing machines and radios into the reach of the middle classes. The motor industry also boomed in the 1930s, in areas around Birmingham, Coventry and Oxford, with the number of cars on British roads doubling within the decade.

In the worst hit areas, however, families were left destitute. Traditional industries of coalmining, shipbuilding, steel and textiles were concentrated in the North of England, South Wales and Central Scotland. Between 1929 and 1932 these industries declined dramatically, as did the industries supplying them. The chain-making industry of Cradley Heath, which supplied chain to the shipbuilding industry was just one of many. In some towns and cities unemployment reached 70%. Jarrow was one of the hardest hit, and caught the public imagination when 200 unemployed men of the town marched the 300 miles to London to hand in to Parliament a petition containing 11,572 signatures.

Being unemployed was crippling, but added to this was the humiliation of the Means Test. Unemployed workers, who had received 26 weeks of benefit had to answer searching and personal questions or risk losing benefit. They had to declare any money that came into the household through earnings, pensions, trade union benefits, help from relatives, even the sale of goods and furniture. Any income, from whatever source, was taken into account. A Grimsby man, for example, had a wife and three children. He received benefit of 25 shillings and three pence (£1.27). His son earned 15 shillings and three pence a week (76p). His daughter earned a pound. Under the Test his benefit was cut off. In Earby in Yorkshire an ex-serviceman and his two sons were denied benefit, because the wife was earning two pounds a week, and the man was in receipt of ten shillings (50p) army pension, having been injured in the First World War. In its first four months of operation the Means Test was being applied to over a million unemployed. By 1932, 377,000 men had been struck off from receiving any kind of benefit.

Adding insult to injury, large numbers of men were forced to leave their families and attend labour camps, if they wanted their wives and children to receive any kind of benefit. The camps were run on military lines, and were supposed to make the men more employable, despite the fact that their was no employment to be had. Pay was just 4 shillings (20p) a week, from which money was deducted for petty offences. By 1938 there were 35 such labour camps, quickly renamed 'slave camps'. Over 120,000 men passed through them.

Rearmament in the face of the threat from Nazi Germany, and subsequently the outbreak of the Second World War finally brought unemployment to an end.

Rollover the captions in the box to see the available images in thumbnail format, click the caption to see the full-size image

| Reference: | 755 |

| Keywords: | |

| Archive Ref: | |

| Updated: | Wed 23 Apr 2008 - 1 |

| Interpretation written by | Barbara Harris |

| Author's organisation | |

| Organisation's website |